Higher education in the United States is expensive. Our presidential nominees debate how to offset costs, banks keep issuing student loans to fresh high school graduates with interest rates toggling between 6.24%-10.99%, and families struggle to make ends meet for the next four years, until the next child is ready to leave for college. This first post in a five-part series explores one of the most misused and misunderstood of these myths: administrative bloat.*

*Full disclosure, I am a college administrator.

The argument du jour regarding the rising cost of higher education is administrative bloat. True, regulatory changes such as Title IX require institutions to bring on more staff, and the demand for higher touch services such as mental health counseling, career advising, and around the clock emergency response systems all drive-up costs. However, the increase of administrative expenditures are not bloat, they are the necessary cost of doing business.

Critics outside of the higher education world may believe these administrative services and their staff to be excessive, extravagant, and beyond the scope of mission of an institution: to educate.

Universities exist to enlighten, provide job preparation and career training, and even undertake cutting-edge research. Critics often fail to consider is that a college campus is essentially a city housed within a municipality. Since a cohort of students live in residence (even during the summer), campuses are in constant use and operation 24 hours a day, 365 days a year. Just to keep the lights on, toilets flushing, the heat running, and roofs from leaking, many institutions must have their own physical plants. These basic needs costs the campus of UMass Amherst, $7.7M annually, or $338.49/student.

Beyond the additional cost and operational needs of housing students (e.g. dining, mail services, housekeeping, maintenance, and the residential staff to keep the place running and a safe living environment), institutions also assume a great deal of risk and responsibility for housing students, be it an 18 year-old undergrad or a third-year law student. The philosophy of in loco parentis, Latin for “in place of the parent” informs, if not controls, the way in which colleges assume liability for their students. Historically, in loco parentis was the means through which institutions could enforce morality codes, especially for women on campus. Dixon v. Alabama (1961) is said to have brought an end to this concept. However, after MIT student Scott Krueger died due to alcohol poisoning during a fraternity event, the re-adoption of in loco parentis has been on the rise and is now being used as a means of liability reduction.

Students, their parents, and the federal government are now holding institutions more accountable for their role in providing a quality learning environment that extends beyond the classroom. For example, after the Virginia Tech shooting, the Family Educational Rights and Privacy Act (FERPA) was amended to allow institutions to share a student’s mental health and physical safety concerns with their parents or guardians (FERPA previously prohibited this action). In a number of law suits, Virginia Tech was found negligent due to its “special relationship” (Commonwealth v. Peterson, 2013) with its students, resulting in over $11M in fines and court settlements.

The suicide of MIT student Elizabeth Shin (2000), a seminal case taught in higher education law classes, brought on a sea change regarding the importance of mental health on college campuses. Though MIT settled out of court with Shin’s parents for an undisclosed amount (the original claim was for $26.45M), it also increased the amount of mental health resources available including more counseling staff and increased office hours, and was made free of charge to students. MIT’s response to Shin’s death was a catalyst for many institutions to change the way they interpret their liability regarding the mental health of their students.

A number of lawsuits have been brought against colleges for poor advising. In Hendricks v. Clemson University (2003), basketball player R.J. Hendricks sued Clemson (Division I) for gross negligence, breach of fiduciary responsibility, and breach of contract after he failed to remain NCAA eligible when transferring from St. Leo University (Division II). The Supreme Court of South Carolina gave deference to Clemson and stated, “We believe recognizing a duty flowing from advisors to students is not required by any precedent and would be unwise, considering the great potential for embroiling schools in litigation that such recognition would create.”

Additional administrative staff have been mandated by the federal government. The U.S. Department of Education’s Dear Colleague Letter in 2011 required all universities to have a Title IX Coordinator in place by the start of academic year 2014. This letter essentially created an entirely new interpretation of the law, moving from gender equity in sports to preventing sexual assault and violence on campus, which required a completely new technical expertise to the field of higher education. Moreover, the Dept. of Education stated it would issue significant fines for institutions that did not correctly follow the new Title IX Guidance for administering sexual assault cases. As of January 2105, 95 schools were under investigation by the Dept. of Education and the Office of Civil Rights for not complying with the new policy, and as of April 2016, ten students successfully sued their college for failing to properly adjudicate rape cases or take proactive measures to prevent sexual assault on campus.

This new version of in loco parentis creates a contract in which institutions are obligated to provide for students’ needs, including advising, mental health support, and emergency responders, and public safety. Many institutions choose to be proactive in their risk and liability management by providing more administrative staff to support students and their various needs. This strategy may be expensive, but it is far less costly than battling a multimillion dollar lawsuit.

Beyond operational costs and liability measures, administrators keep institutions running. Robbie Hiltonsmith, a senior policy analyst and author of a 2015 report on college affordability, argues the concern of administrative bloat is misplaced. In an interview with Inside HigherEd regarding the findings of the study, Hiltonsmith stated, “A lot of these people are necessary. For every second assistant dean that people complain about, there’s also an additional counselor or an additional financial aid person or an additional IT person. And all of these things are necessary to support the growing university. There aren’t a lot of efficiencies to be made—this does need to increase proportionally.”

According to The National Center for Educational Statistics, college enrollment rose by 31% from 2000 (13.2M students) to 2014 (17.4M students), and will continue to increase by 14% between 2014-2025. These additional 2.4 million students will also require academic advising, financial aid counseling, library services, dining, public safety, etc., not mention the things that make college the supposed best days of your life like student organizations, intramural sports, Greek Life, and new student orientation. All of these aspects of a college campus require administrative oversight. They are not bloat, they are what make an institution work.

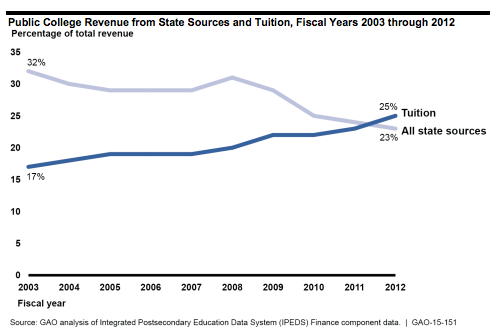

Follow me to learn more about my next post and the second myth behind the rising cost of college: the price tag of public colleges and universities has risen exponentially.

What MOOCs must do to Remain Relevant in American Higher Education

What MOOCs must do to Remain Relevant in American Higher Education