As the four previous articles in this series demonstrate, running a college is not an easy or inexpensive venture, and fixing the problem of the cost of college requires more than one magic bullet. The last myth in this series is not another piece of the puzzle, but rather image these pieces create: the cost of college is only worth the job it lands the graduate. In other words, America’s expectation of the ROI of a college degree has changed.

For example, U.S. Senator Ron Johnson (Wisconsin-R) made quite a splash this past week during an engagement with WisPolitics when he said, “We’ve got the Internet—you have so much information available. Why do you have to keep paying different lectures to teach the same course? You get one solid lecturer and put it up online and have everybody available to that knowledge for a whole lot cheaper? But that doesn’t play very well to tenured professors in the higher education cartel. So again, we need disruptive technology for our higher education system.” He continued, “If you want to teach the Civil War across the country, are you better off having, I don’t know, tens of thousands of history teachers that kind of know the subject, or would you be better off popping in 14 hours of Ken Burns Civil War tape and then have those teachers proctor based upon that excellent video production already done?”

While Sen. Johnson makes a fair point that higher education would benefit from some disruption (e.g. MOOCs), his comments reflect a dramatic shift in tone regarding our societal expectations regarding the purpose and value of postsecondary degree.

In a post-recession economy, the value of a college degree comes not from the experience of going to college, but the opportunity, or more specifically—the job—it will yield. Thus when we believe a college degree’s utility is for career preparation, it only follows that we should be critical when the return does not equitably match the investment.

Some have argued that perhaps the cost of tuition should depend on the type of degree the student is seeking and their potential earnings. Others argue that cutting out general education requirements will allow students to matriculate faster without incurring more debt. These ideas may have merit and be the disruption Sen. Johnson calling for, but the cost of going to school degree is not directly correlated to the by-product.

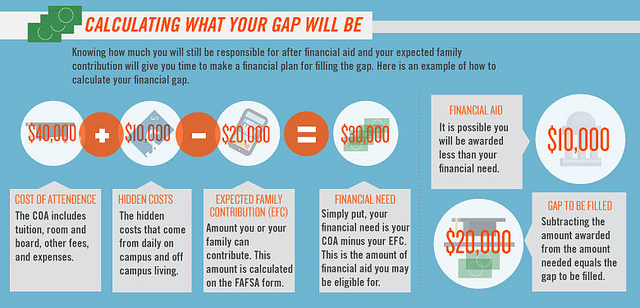

It may be true that the postsecondary degree ROI is no long as strong a guarantee to land a job upon graduation, but the call to reduce the investment burden on the student fails to recognize that the cost of going to college is inclusive of actually going to college.

When thinking strategically about reducing the cost of both direct and indirect costs, it is short-sighted to only think of short term gains of graduates being able to land a job. College graduates, regardless of when they find full-time employment, still out earn high-school graduates, and a 2014 Pew study reveals that 86% of Millennials that took out loans to pay for school do believe that the cost of going to college is worth the mobility it will provide them in the future. Moreover, regardless of the means by which individuals use to pay for their postsecondary the degree, the market is bearing current tuition rates. As long as demand is high, so will be tuition.

So, is college too expensive? Maybe. Maybe not. But when solutions call to reduce the quality of the education for the purpose of cutting costs, the inherent value of a college degree becomes diminished, and respectively reduces the ROI, thus only exacerbating the problem.

I’m not sure what the solution is for cutting college costs, but I know it’s not Ken Burns documentaries. . . on tape? That said, his miniseries on the Roosevelts was quite compelling.

5 Myths Behind the Rising Cost of College in America: Part 4

5 Myths Behind the Rising Cost of College in America: Part 4